Over the years, Apple has built up a portfolio of services and add-ons that you pay for. Starting with AppleCare extended warranties and iCloud data subscriptions, they expanded to Apple Music a few years ago, only to dramatically ramp up their offerings last year with TV+, News+, Arcade, and Card. Their services business, taken as a whole, is quickly becoming massive; Apple reported $12.7 billion in Q1 2020 alone, nearly a sixth of its already gigantic quarterly revenue.

All that money comes from the wallets of 480 million subscribers, and their goal is to grow that number to 600 million this year. But to do that, Apple has resorted to insidious tactics to get those people: ads. Lots and lots of ads, on devices that you pay for. iOS 13 has an abundance of ads from Apple marketing Apple services, from the moment you set it up and all throughout the experience. These ads cannot be hidden through the iOS content blocker extension system. Some can be dismissed or hidden, but most cannot, and are purposefully designed into core apps like Music and the App Store. There’s a term to describe software that has lots of unremovable ads: adware, which what iOS has sadly become.

If you don’t subscribe to these services, you’ll be forced to look at these ads constantly, either in the apps you use or the push notifications they have turned on by default. The pervasiveness of ads in iOS is a topic largely unexplored, perhaps due to these services having a lot of adoption among the early adopter crowd that tends to discuss Apple and their design. This isn’t a value call on the services themselves, but a look at how aggressively Apple pushes you to pay for them, and how that growth-hack-style design comes at the expense of the user experience. In this post, I’ll break down all of the places in iOS that I’ve found that have Apple-manufactured ads. You can replicate these results yourself by doing a factory reset of an iPhone (backup first!), installing iOS 13, and signing up for a new iCloud account.

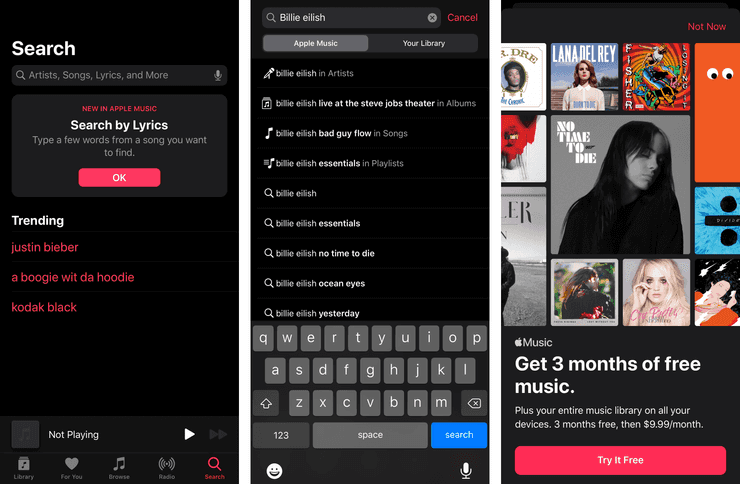

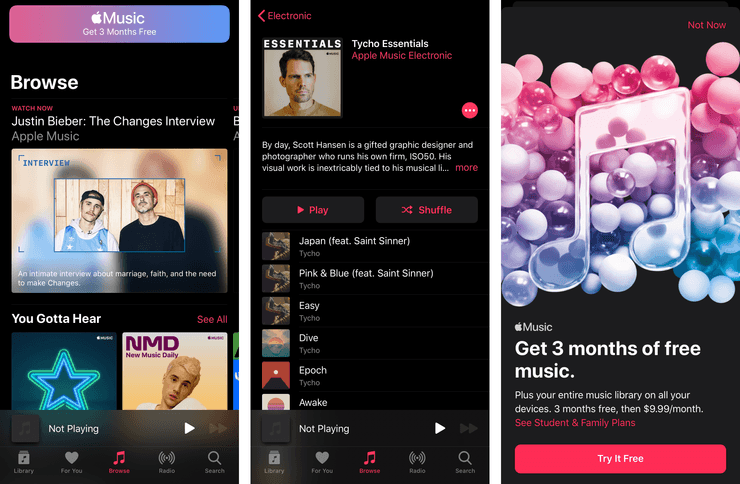

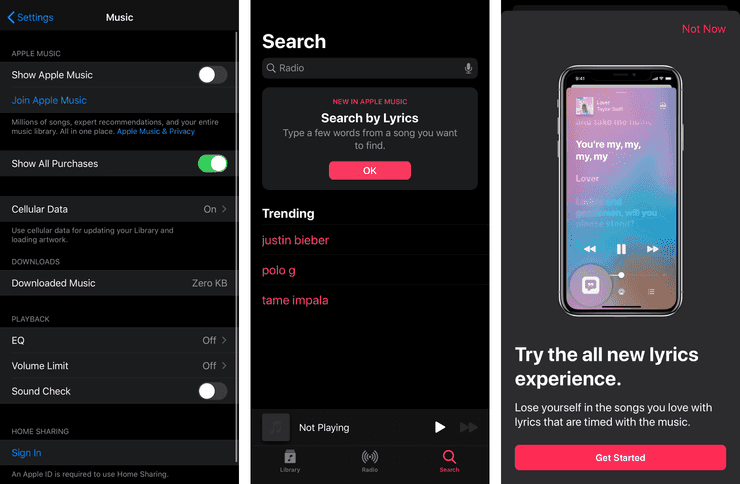

Apple Music

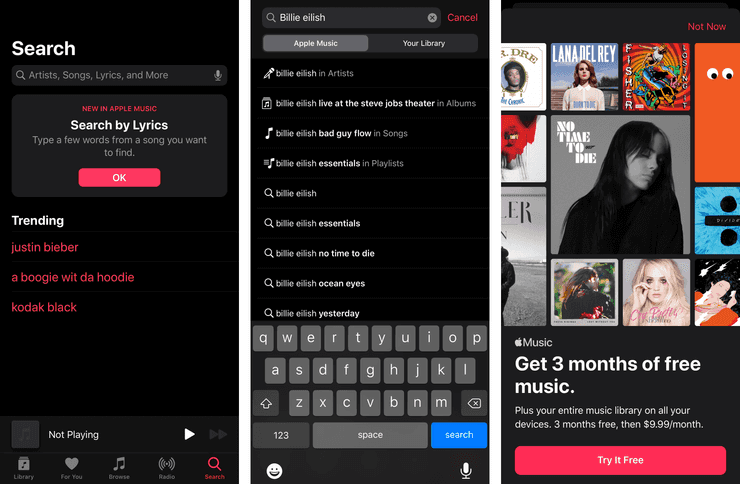

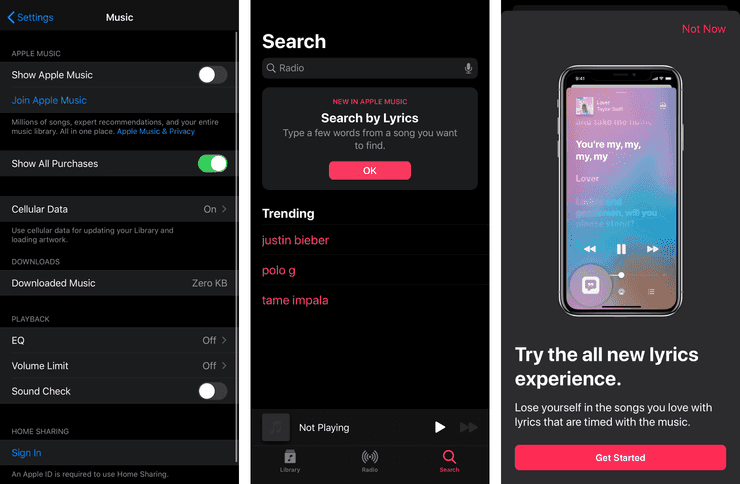

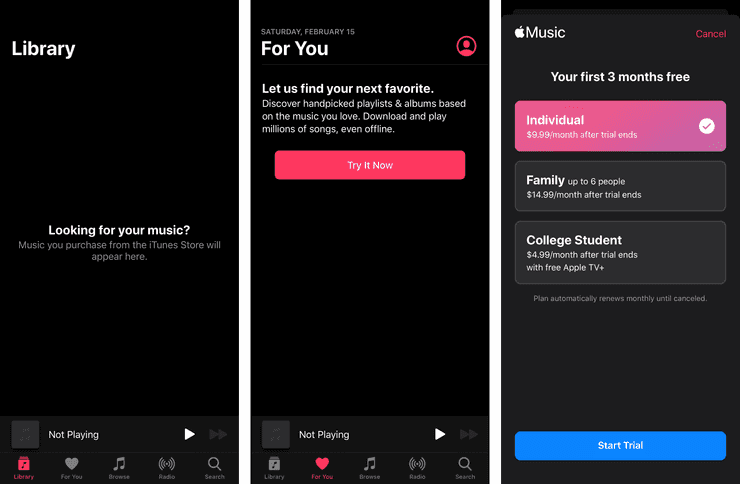

When you open the Music app for the first time, it shows you an empty library and a bit saying that you can get music from the iTunes Store. So you head over to the search tab (ignoring the “Search By Lyrics” ad for Apple Music), and search for an artist, and find that your library is empty, but that Apple Music search tab sure is full of lots of exciting stuff. You navigate down to the song you want to listen to, and you get greeted with a fullscreen popup ad for Apple Music, one which went out of its way to disable support for iOS 13’s new swipe-to-dismiss gesture.

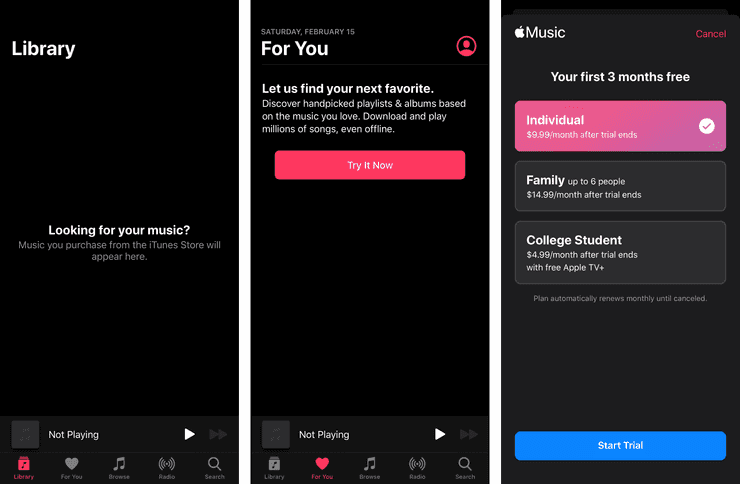

Leaving search, there are three other tabs at the bottom: For You, Browse, and Radio. The “For You” tab is a sneaky ad, offering to help you find new music based on your tastes. Tapping the big red button takes you to a signup screen for Apple Music. Nowhere on this screen was it stated to be a subscription feature.

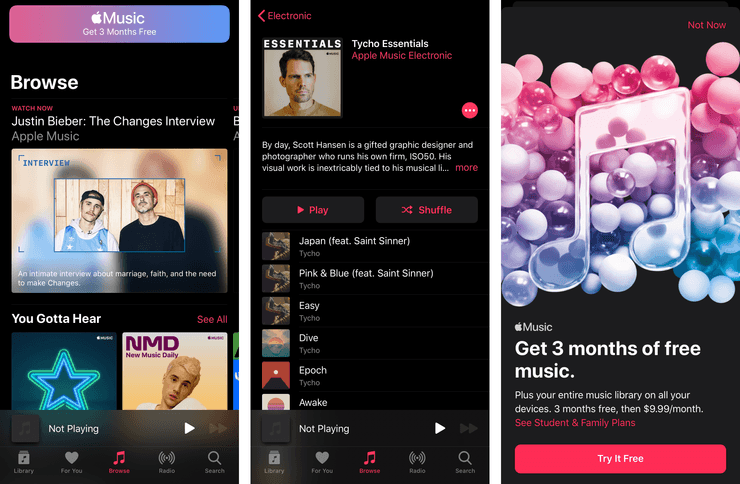

Under Browse, you find a whole selection of songs, artists, playlists, and other general curated music selections. Tapping into basically anything will take you to a fullscreen Apple Music ad.

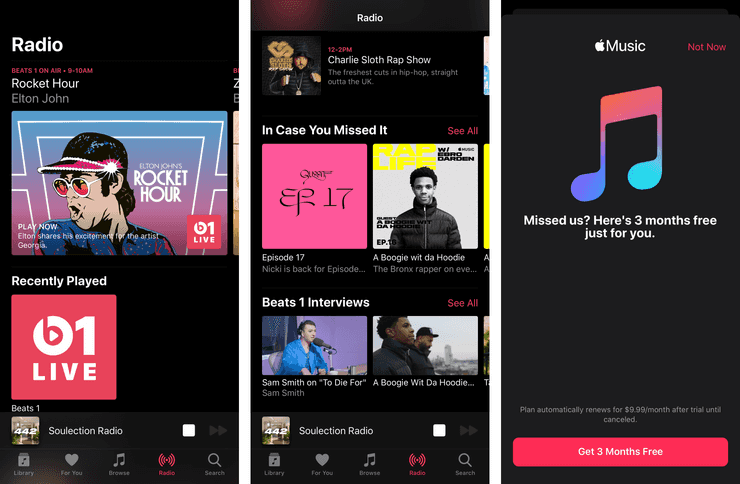

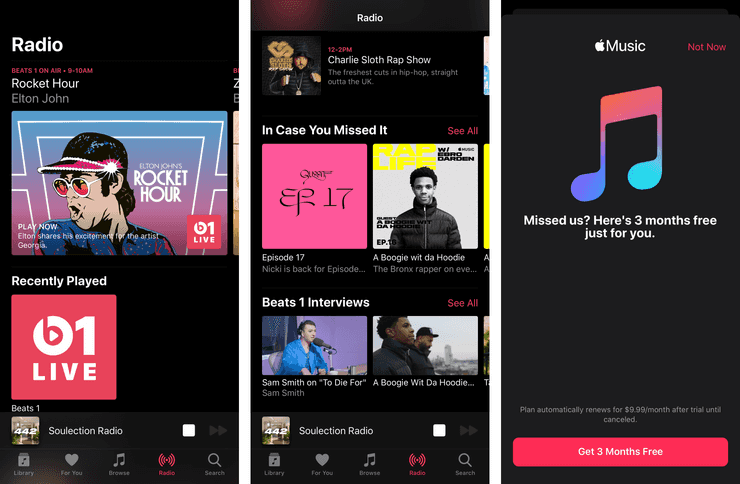

In Radio, we finally have something we can tap that doesn’t trigger an Apple Music ad! Beats 1 can be played seemingly without subscribing to Apple Music, and some of the older interviews are playable. I say “some”, because while tapping on that interview of A Boogie Wit Da Hoodie will play, tapping on the entry for A Boogie Wit Da Hoodie under the “In Case You Missed It” section will bring up another fullscreen ad.

As a bonus, it stops whatever you’re playing, as the audio player switches to the track you selected before the server tells it that it can’t be played without a subscription. I think this is a bug more than malice, but it highlights how the app is designed for the subscriber, not the person who doesn’t want Apple Music.

So Browse and For Now are entirely Apple Music ads. Radio has some free content but that largely exists to pull people into Apple Music, and Search will happily pull you in to Apple Music if you tap the button. Almost this entire app serves to be an ad for Apple Music. There is a setting in the Settings app to hide Apple Music (next to an ad for Apple Music, of course), but that only does so much.

The Browse and For Now tabs are hidden, and some of the Apple Music-exclusive stuff in Radio is hidden. But every radio station except for Beats 1 is still present, all which trigger an Apple Music ad. After you quit and restart the Music app, the search bar changes the “Apple Music” search results to “Radio”, but the autocomplete largely populates from Apple Music, and some of the search results can return playlists that take you to Apple Music. It helps, but ads are still there to be stumbled into.

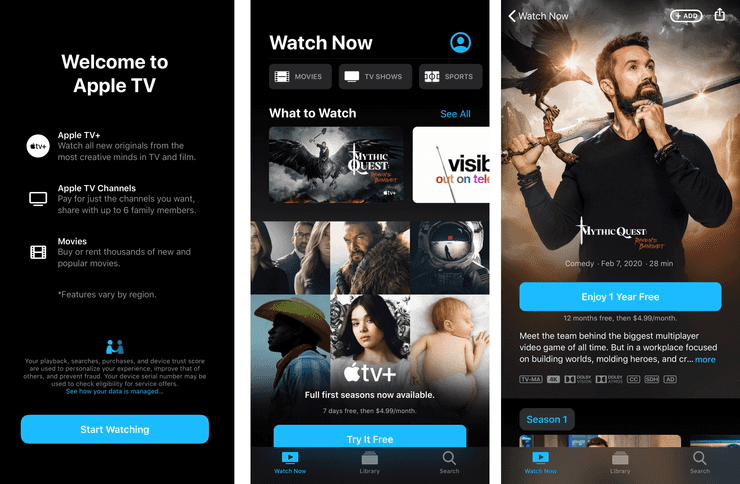

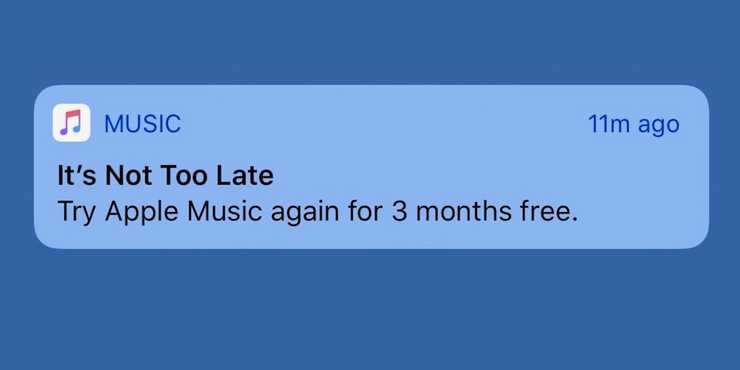

If you subscribe and then cancel, Apple sends invasive push notifications asking you to re-susbscribe. These are on by default without a permission request. This is, of course, against the rules they lay out for other developers.

Push Notifications must not be required for the app to function, and should not be used for advertising, promotions, or direct marketing purposes or to send sensitive personal or confidential information.

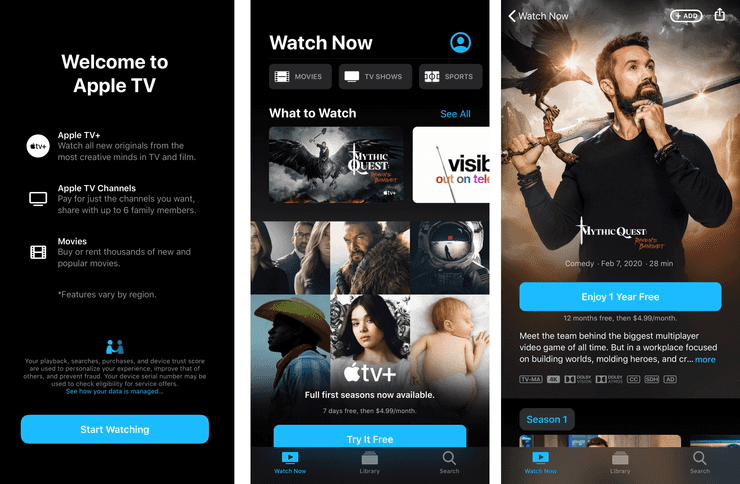

Apple TV+

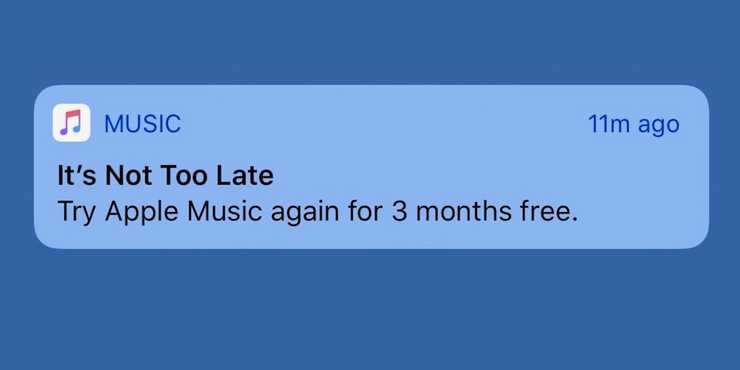

The TV app opens with Apple’s standard summary screen, leading with an ad talking about Apple TV+. The home screen is chock full of TV+ ads and ads for shows on TV+. If you have existing iTunes Store shows, or streaming apps like Netflix or Crunchyroll setup, you might see shows you’re watching under the “Up Next” section. But no matter what you have, the Apple TV+ ads are huge and inescapable. Again, the TV app’s notifications is enabled by default with no permission request.

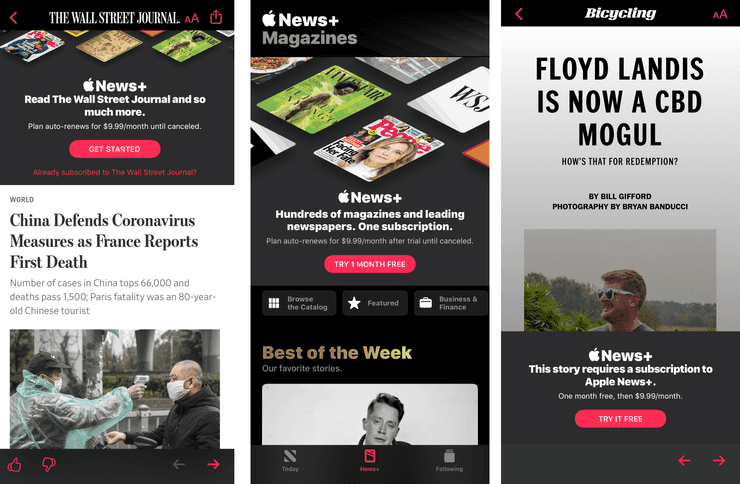

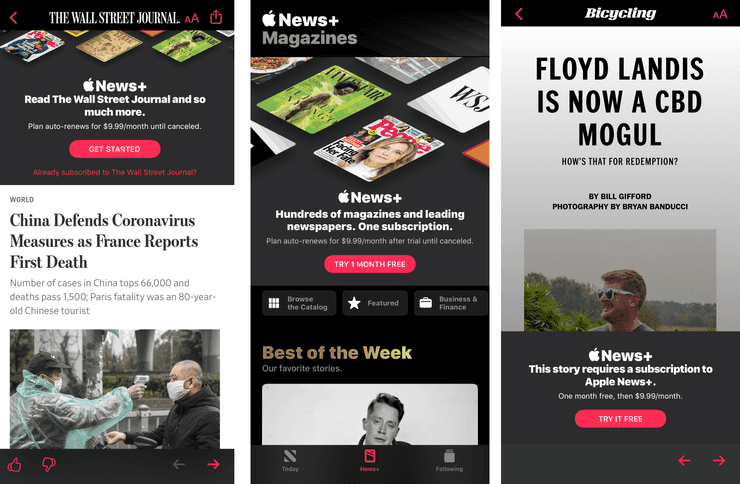

Apple News+

Another app that has its notifications turned on by default, this is how many people will interact with this service. Tapping notifications doesn’t take you to a web browser, but directly into the News app. If you open a story on one of Apple’s partners like the Wall Street Journal, the screen it takes you often has a large banner ad at the top of the screen for the Apple News+ service. This seems to be intermittent, but it cannot be dismissed, hidden, or disabled.

If you look through the News app itself, you will see a plethora of stories in the Today feed. Some of these will trigger the same ad shown above; there is no indication on the feed itself. Some will actually have a full paywall in front of them preventing access without signing up; these do have a tiny Apple News+ logo beneath them, but it’s far enough below that it almost looks like it belongs to the next section.

And of course, in the dead center of the tab bar, is the News+ tab. Leading off with a large ad at the top of the feed, it lists stories and publications similar to the Today feed. Most of these stories are paywalled, but not all, so people may end up going there and hunting for stories they can read. This tab cannot be hidden, ever.

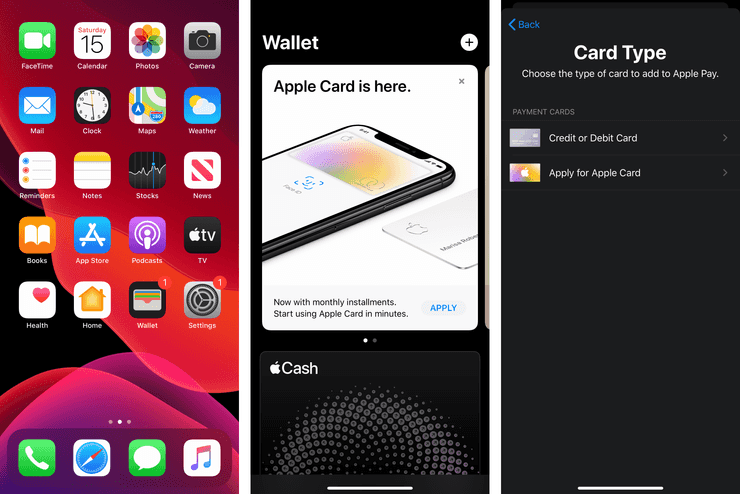

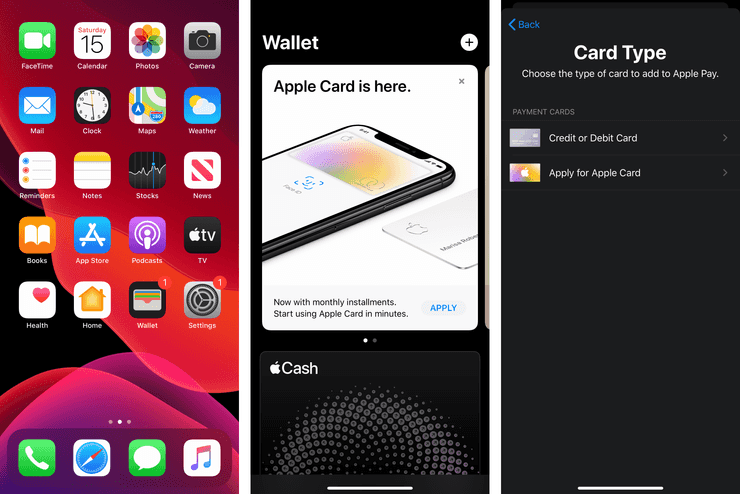

Apple Card

After you set up your iPhone, you get a home screen with at least one badged icon, on Wallet. Opening this takes you to a giant ad that’s nearly half the screen for Apple Card. Fortunately it is dismissable. But every time you try to add a credit/debit card to Apple Pay, you are asked if you want to sign up for Apple Card instead.

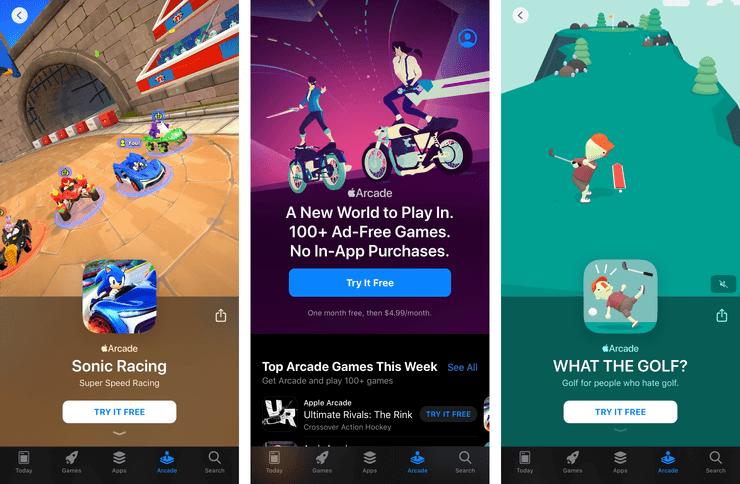

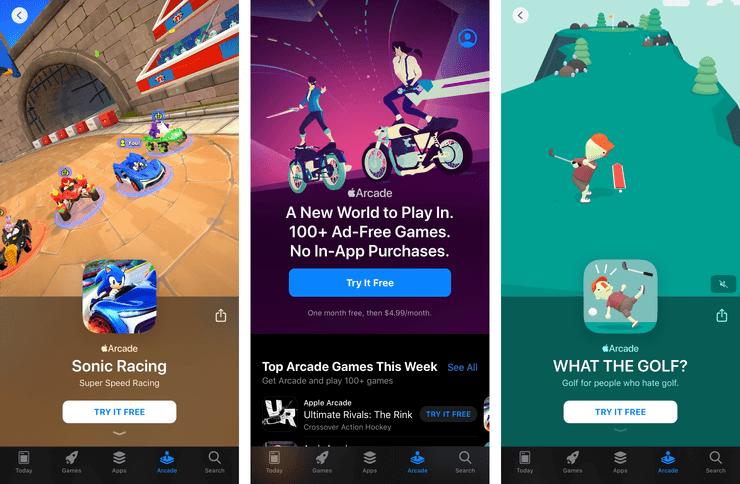

Apple Arcade

The first three tabs of the App Store app are Apps, Games, and Today. These tabs don’t have much in the way of ads, aside from some Apple Arcade games that might appear in Games and Today. However, Apple Arcade gets an entire tab all to itself, which has a huge in-feed ad for the service, and of course a whole pile of games advertising it. Compared to other games and apps, Apple Arcade games get more prominent visual treatment, larger videos, and bigger download buttons. This tab, like News+, cannot be turned off.

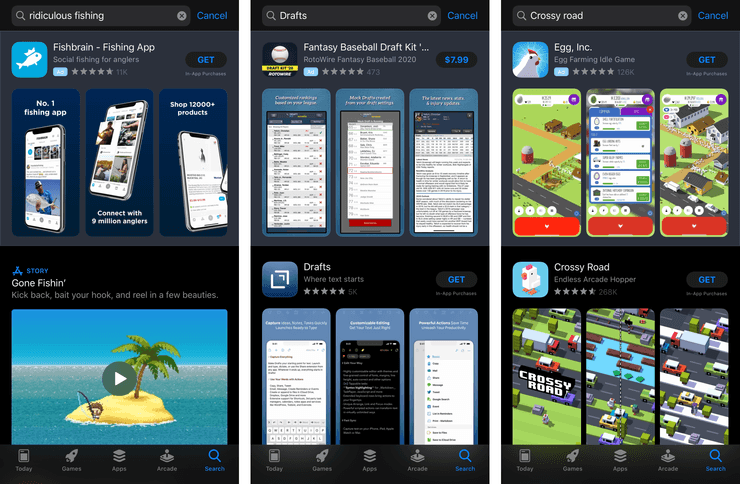

App Store Search

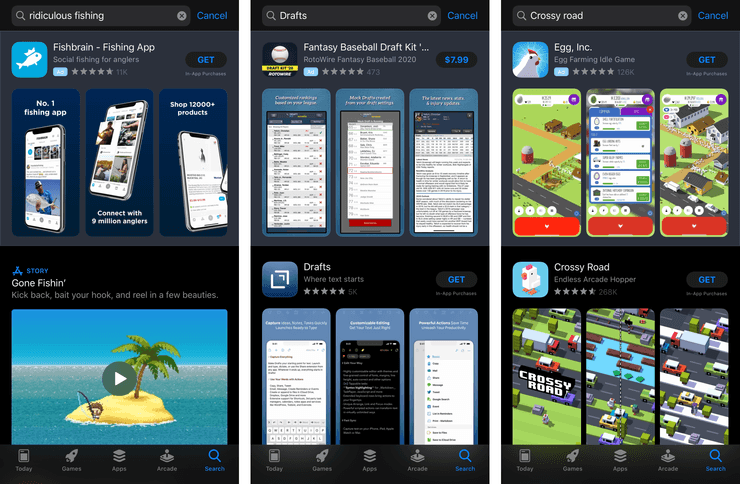

And of course, almost anything you search for in the App Store has a large ad at the top of your search results. This isn’t an ad for an Apple-run service, but it is a way they make money by extorting developers and showing you the wrong thing. If you search for a specific app, you will often not see that app in the first slot, unless the developer has paid for the privilege.

Conclusion

Apple wants to grow their services business with drastic increases year-over-year. This means they are going to aggressively push more services into more places (including deeper into macOS and tvOS, which are also slowly having adware trickled into them). Apple TV+, News+, Arcade, and Card are all new this year, and are already strongly advertised in iOS. Apple Music has existed for a few years, and its level of advertising in the app is pervasive. As time goes on, these ads are going to get worse, not better.

Of course, Apple has a right to tell users about their services, and try to convince you to subscribe to them. And you might disagree with my assessment that some of these are ads at all. Individually, most of these instances aren’t insidious by themselves. But when you look at them together, they paint a picture of how Apple is making the user experience provably worse to boost growth at all costs.

This issue is not going to get better. Apple is going to expand its services, both breadth and depth, and the adware problem is only going to get worse, unless people call out Apple for what they’re doing. And yet, this issue is rarely talked about, likely because many of the people who cover Apple inevitably subscribe to some or all of these services. Gadgets like smart TVs and ebook readers are frequently criticized for their annoying, invasive advertisements despite their (often large) upfront price. It’s time for the tech community to recognize that Apple is no longer designing their products for a great experience, but as upsells to get you into the paywalled garden.